Dreaming of Horses

The road past Fox Hollow Farm darkens in the Illinois cornfields until the blacktop disappears. Still there’s no sign of a trailer. The security lights at the next farm switch on, casting a lonely glare. It's quiet, and I stand by the front gate, so the truck won't miss the driveway. At almost sixty years old, a lifelong dream is about to come true.

As I think back, I can see myself at five, wearing clumsy brown shoes, dodging low-hanging clotheslines, and running as fast as I can. It’s early in the morning in Tokyo, Japan. The year is 1948, and a man and woman are riding towards me on horseback over the raw mud and new sidewalks of an American military housing project. The horses, one white and one bay, look enormous, and they are the most beautiful animals I have ever seen.

Grant Heights, Tokyo Japan, 1948 (Photo copyright Col. Guy O. DeYoung, Jr.)

Postwar Japan is a place of apparitions, many of them startling and sad, but not the horses. They are magnificent. The riders, who don't notice me, pass like royalty. In the days that follow, I haunt the muddy yards, hoping in vain that the horses will return. This is the beginning of a love affair that will be unrequited for most of my life.

The mothers who arrive with wet laundry in the mornings shoo me away. Horses and riders are just more strange visions in Grant Heights, the quarters the Army has built for its families. Our kitchen window has a distant view of Mt. Fuji, Japan’s most famous landmark, but it does not overlook the firebombed city of Tokyo. I have seen the burnt buildings when Mother takes us downtown to church on Sundays.

In its own way, the countryside is scarier. It’s dotted with large concrete bumps. Mother says they were once bomb shelters. Now they are homes. The Japanese are walking the roads. Some of the people are incredibly old and bent under great loads of wood.

Air Raid Shelter near Grant Heights, Tokyo, Japan, 1950 (Photo copyright Col. Guy O. DeYoung Jr.)

Life here is vastly different from anything I have ever known. Two maids and a houseboy live with us. The servants bring groceries, but no one in our family may eat the local food. We eat canned or dried food from the Army commissary. We don’t like it much, but when we complain, Mother reminds us of the honey buckets, the human excrement the Japanese are using in their fields. The food grown here isn't safe to eat.

A cart carries human waste for fertilizer. Tokyo, February, 1950.

(Photo copyright Col. Guy O. DeYoung, Jr.)

Japan has lost a war with the United States. Our parents have told us that. Our father, a young colonel from the battlefields of Europe, has come to Tokyo with the American commander, General Douglas MacArthur. Occasionally, we go with Mother to the general's headquarters, the Dai Ichi Building, to pick up our dad. Sometimes, we see large crowds of Japanese. They are quiet and polite, but I’m afraid of them.

"Didn't they lose?" I ask my mother. "Aren't they mad at us?" "They admire soldiers," she says. "They like the general."

But this cannot be completely true because my parents stop me as I start to step up into a passenger car of a train we are taking for a family outing.

“Not that car,” they say. “It’s not safe to ride with Japanese civilians.” Instead, we climb into a box car and sit on our suitcases.

A child does not have to accept such a world.

I see things – temples, kites, parasols, and now the horses -- that seem magical. I imagine other worlds and hope to make some connection.

o DeYoung, 5, reluctantly arrives in Ito, Japan, with brother Willis, 3, and parents Lt. Col. and Mrs. Guy O. DeYoung Jr. (Photo copyright Colonel Guy O. DeYoung Jr.)

We go to Izu for a stay at the Kawana Hotel, built before the war to look like an English country estate. The hotel has survived unscathed. Its vast, inviting lawns slope toward the sea.

Our parents play golf with the Australians. For many years, Mother and Dad will tell the story of Mr. Oybee, a jovial bon vivant who regales them over drinks with tales of life Down Under. At the end of the vacation, when they exchange addresses, they will ask Mr. Oybee to spell his name.

"O-B-R-I-E-N," he says, and they explode with laughter. “So far apart in the same language,” they say.

Playground at the Kawana Hotel, Ito, Japan, November 1949 (Photo copyright Col. Guy O. DeYoung Jr.)

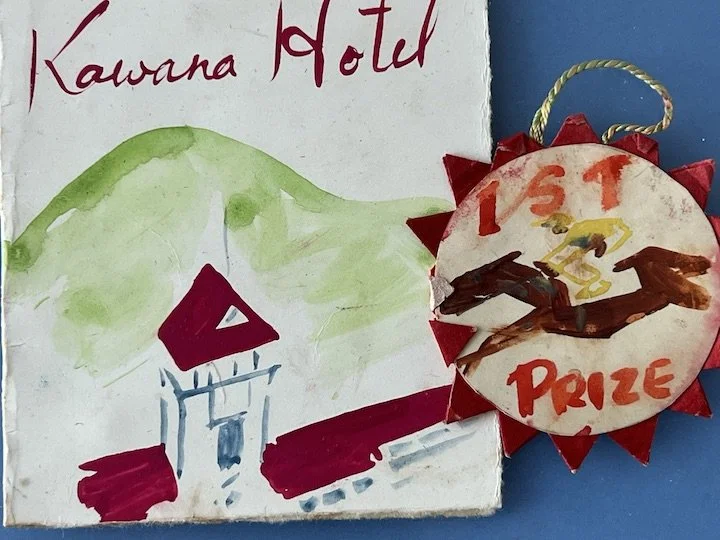

Each day, until the end of cocktails and dinner, we stay in the nursery, even though I tell them I am five, too old for a nursery. But I do enjoy the horse races. It’s played with horse heads as tall as we are, named after the greatest thoroughbreds of the day. We draw numbers to move them across the floor.

I know nothing about racing, but I pick Sea Biscuit and memorize the names of the others because horses are important to me: Count Fleet, Citation, War Admiral, Man O' War. Sea Biscuit wins first place and a small blue ribbon. My brother Billy, a toddler, wins second place and a red ribbon on Citation.

Mementos from Childhood Nursery Games at the Kawana Hotel 1949

In the distant future, decades after Billy dies from leukemia as a young Army officer, twenty-six years old, the small blue and red ribbons will reappear in waxed paper, tucked among letters from Mother’s estate.

One day during our stay at the hotel, we children are taken for a walk in the gardens. Near the end of a gravel path, the Japanese nursemaid points out a circle of rocks, set back to the trees.

"The fairies and their king and queen come here at nightfall," she says, looking at me. She knows I love the horse race game. "They ride in a coach drawn by tiny horses."

Back in the nursery, I think about the fairies and the tiny horses. I wait for a chance and lead Billy out a side door when the nursemaid isn't looking. It's getting dark, but the fairy circle is easy to find. I am overjoyed that the fairies have not yet arrived. Billy and I sit down on the rocks to wait. Then I tell him stories to pass the time, but the fairies and their tiny horses do not appear.

When it's very dark, Billy wants to go back to the hotel, but I do not want to give up.

“Maybe we’re scaring the fairies,” I say, and we walk into the trees to hide. In the distance, we can see the lights of the hotel, but the blackness around us is now complete.

Small, dancing lights appear. Then we hear shouts. The lights grow larger and approach, and we hear our names. We run out of the trees, both of us crying. Billy cries because he wants Mother. I cry because I know I’m in trouble, and I haven’t seen the fairies.

I don’t imagine they're just a story. I’ve failed somehow, and I will not see the coach or the tiny horses. Not this night. Not ever. But other worlds still co-exist, beautiful worlds where horses are important, as I will see.

Cherry trees at the entrance to the Imperial Palace gardens, April 12 1950

(Photo copyright Col. Guy O. DeYoung, Jr.)

Post World War II Ruins of the Imperial Palace, Tokyo Japan, April,1950

(Photo copyright Col. Guy O. DeYoung, Jr.)

Shortly before we are to leave Japan, an invitation arrives from the Imperial Palace. The colonel and his family are invited to a garden party there. Father wears his uniform, and we wear our best clothes.

On the way, our parents give me the kinds of instructions you might read in a fairy tale. Once we arrive at the palace, we are not to eat or drink anything we are given, no matter how delicious or how tempting. But we are not allowed to say that the food has been forbidden. Instead, I must say "Thank you. I'm not hungry."

Billy is too little to understand, so I must watch him and keep him away from the food. I am now six. It doesn't occur to my parents that this task might be too much for me.

To the amazement of Billy and me, there's a moat, and the palace gardens are so crowded and exciting that we don't think of food at first. The Japanese women are kind and lovely, dressed in traditional clothes, silk with bright colors. Their eyes and hair are beautiful.

Billy and I are blondes: Billy has his grandmother's platinum hair, so white that a curious crowd once gathered to touch his hair when we went to the zoo. My curly hair is a deeper shade of blonde. I hate my hair. I want dark hair like Mother’s, or even better, straight black hair like the Japanese.

The women at the garden party make a fuss over us, and I hold Billy’s hand. Eventually, we are guided to tables laden with fruit and things to eat. I see peaches and remember the sweet taste of a peach I once ate in Virginia, a deed remembered in family stories because it's never been truly forgiven. The brown stains from the peach juice ruined the white organdy dress my mother had spent weeks smocking by hand.

Now, after eating fruit only from cans, I want a fresh peach more than anything I can imagine, but I tell the women, "Thank you. I'm not hungry," and look away. Billy, however, reaches out. He wants to eat, and when I catch his hand, he starts to cry.

It's clear to the women that something's wrong, but they smile gently and beckon a man who comes over and tells us he will take us to see something wonderful.

Our parents have vanished into the crowd of ladies and officers, so we follow the man out of the gardens and toward some buildings where the man motions for us to wait. Suddenly, we see a creature more beautiful than any fairy horse and much, much bigger. A white horse is led out of the stables to stand perfect and gleaming in the sunshine. He is stately and quiet, and we are told that he belongs to the emperor.

Hatsuyuki, White Horse of Emperor Hirohito of Japan on April 12, 1950

(Photo copyright Col. Guy O. DeYoung Jr.)

As I will learn, his name is Hatsuyuki or “First Snow.” He is not the white stallion the Emperor rode at the head of his troops. That was Shirayuki, or “White Snow,” who is dead. Nor is he the white stallion Hatsushimo, or “First Frost,” seized by the Army and sent to the States.

Hatsuyuki is an Anglo-Arabian (part purebred Arabian and part Thoroughbred). He has the height of a Thoroughbred and the color of an Arabian, a gray coat that has turned white with age. He is a gelding, making him more docile than a stallion and the Emperor’s favorite riding horse.

In the near future, in December 1952, he will be dedicated as a shinme, a sacred horse, and leave the palace stables to live at Isa Jingū, Japan’s central Shinto shrine. In doing so, he will join an equine religious tradition over 1200 years old. He will be adorned for ceremonies but never ridden again until he dies in 1957 at 23.

(For an excellent history of the Emperor’s white horse, including Shirayuki’s birth in California and Hatsushimo’s career as a rodeo horse in America, see Judi Daly’s article on the Long Rider’s Guild Academic Foundation website.)

(For the shinme, see this eloquent and detailed account: Sakamoto Naoko, “The Key Attribute of Shinme Sacred Horses Dedicated to Ise Jingū since 1865” in Religious Studies in Japan, Volume 4:3–22)

Just as a child who has not experienced war cannot imagine its true horror— even a child who has glimpsed its aftermath—so it will be years before I can understand the significance of our encounter on this April day.

Here is Emperor’s white horse, the avatar of a dream of power that ignited a war that drowned the Pacific in blood. Here are two little children of the American military who dropped history’s first atomic bombs and annihilated two Japanese cities.

We meet in the Emperor’s gardens, the physical and symbolic heart of the conflagration, all of us innocent and unaware. It is April 12, 1950, and a spring day is in bloom. Peace is starting to blossom.

When my father hears of the horse, he is invited to see for himself and takes several photographs that eventually make their way into the family album. His remarks are more reminiscent of a farmer than a historian or philosopher. He writes that the horse is “Seventeen years old. Very gentle. Absolutely and completely white.”

Jo, Billy, and Mother

Not long after this visit, we journey by ship across the Pacific, home to my grandparents' house in California. On board, with nothing to do, I discover Black Beauty, a novel told from the point of view of a horse, and I read it several times. Published in 1877, it urges those who own and handle horses to train their animals with gentleness and treat them with kindness, taking their feelings into account.

It’s an idea I hold onto, despite the considerable number of people I will meet over the years who will insist on the importance of “showing a horse who’s boss.” As time goes by, I will read shelves of books, collect pictures and postcards, and make countless drawings of horses, too many— even—to throw them all away.

Shortly after we arrive in California, a friend invites my family to Pasadena to see the floats and the palominos with the silver saddles in the Rose Parade, but at the last minute, we children are left behind. Seeing my disappointment, the friend later brings me two tiny flat plastic horses, one black and one nut brown, stamped with bridles and English saddles.

They are so small I can close them in my fist. I keep them on my pillow. As I walk to school through a vacant lot, I imagine I am riding them down the path. Synthetic as they are, they are real in a way my ever-shifting life as an Army daughter rarely is.

There is a dreamlike quality to the new homes, new schools, new teachers, and new neighbors who materialize and disappear as our family shuttles from coast to coast. My brother and I have imaginary friends.

I call my friend "the Cheeseman." I make a hat from a cottage cheese container so I can look like him, and my dad takes a picture. Billy calls his friend "Ba Black Sheep" but refuses to describe him.

One day when we are driving down a two-lane road in Missouri, Billy cries, "Ba Ba!" and points. We look and see an old man driving a cart and a mule. We all wave at him, but my father doesn't stop the car. We children have two grandfathers, one on each coast, but we rarely see either.

We spend one summer in an attic in Kansas, where it’s unbearably hot, and we have the measles. During the Korean War, we live in California with our mother and grandparents while our dad goes to the war. When he comes home, we live in an apartment in Norfolk, Virginia, where a sister is born.

We acquire friends and pets and leave them behind. The legs of my model horses—china, plastic, bronze—break in their boxes with each move until they disappear entirely from a dock in Brooklyn.

When my dad is stationed at the Pentagon in the early days of black and white television, we live for a time in Clarendon, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, D.C., where "Pick Temple" is a local children's television celebrity. He shows western movies, and each day he lets one lucky child from the studio audience sit in the western saddle affixed to a fence on the set. I dream of being chosen to sit there. It doesn't occur to me that some children have real ponies and real horses.

Billy and I have stick horses with fat stuffed heads, manes of yarn, and reins of plastic. A hedge next to the house makes an arch they call Eagle Pass. One wonderful day, our mother takes us to Hecht's department store, where children can be photographed riding a pony. Our mother is afraid of ponies, but she lets us get on. She doesn't buy the pictures. Later, Billy takes up baseball. I ride my bike but pretend it’s a horse.

There will be, briefly, real horses my life. My father hints of this when he stops to say good night and tells me we are moving to Louisiana in a few weeks. He’ll be stationed at Camp Polk, and we’ll live in the country this time, he says, in a house by a lake. Perhaps—just perhaps—I can have a horse. I lie awake most of the night, thinking up the perfect choice. I want a young mare, about four years old. For color, I decide on dappled gray.

In Louisiana, the lake is fetid, contaminated by the septic fields that bubble up black through the grass behind the houses. In an extraordinary stroke of luck, Billy and I once catch a bass in the lake, using nothing more than a safety pin, bread, and a string, but it is the only living thing anyone ever finds in the water. Snakes live on the banks of the creek that feeds into the lake. We see them, twisting and slithering, below a wooden footbridge over the creek.

We imagine the worst---water moccasins, rattlesnakes, coral snakes--- but we never really know. When we are bitten, it is by mosquitoes and yellow jackets and the ants that build colonies with entrances that tower over the ground like chimneys. Twin Lakes, as it is called, is bordered by woods, a tree farm, and fields of peanuts. There's not a horse in sight, only a dusty mule that is brought out occasionally to plow.

At our new school, where many of the children don't have shoes to wear, the teacher asks every day if we’ve taken baths and brushed our teeth at home. If we say yes, we get stickers shaped like bars of soap and toothbrushes to put on a chart on the wall. I’m proud of my row of stickers until I realize that other children have only a few stickers or none at all. Then I am ashamed.

Our family gets a dog, a border collie named Laddie, who becomes Billy's best friend. Finally, one magical day, my dad announces he's buying me a horse. A sergeant who moonlights as a horse dealer suggests several possibilities, and my dad, who doesn't ride, chooses a stubby brown and white pinto gelding named Shorty.

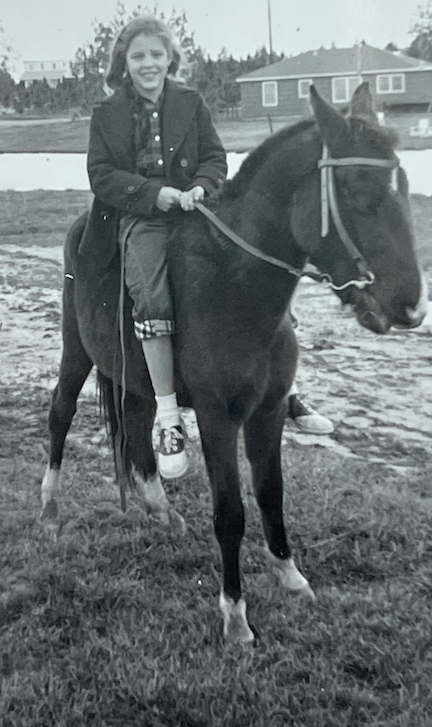

Jo DeYoung, 9, riding Shorty in De Ridder, La, 1953 (Photo copyright Col. Guy O. DeYoung Jr.)

The $35 price for Shorty includes a bridle and a western saddle. Shorty's owner throws in an old Army blanket to go under the saddle. The sergeant drops the horse off in the back yard, and we lease space for him in a pasture on the other side of the woods.

Shorty doesn't like people, especially children, but I don’t realize this. I don’t see that he is swaybacked and ugly, a horse that a fair-minded person might call a nag. Shorty whirls and kicks when I try to catch him for a ride, but I believe he'll get over this. I forgive him when he bolts and tries to run under tree branches when I’m riding him.

One afternoon, he does finally scrape me off by running under a clothesline that catches me under the chin. Fortunately, I’m riding bareback and slide off before I know it, instead of breaking my neck, as might have happened if I had been in my western saddle. At dinner that night, my parents see the red rope burn that runs across my throat from ear to ear.

That's it, they say, the last straw, but I beg to keep the horse and promise never again to ride through anyone's back yard.

No one notices the spare-time activity that is ultimately Shorty's downfall. Unseen, he has spent hours leaning against the fence posts in the pasture and finally pushes one to the ground while I am at school. All the horses escape to run up and down the four-lane highway.

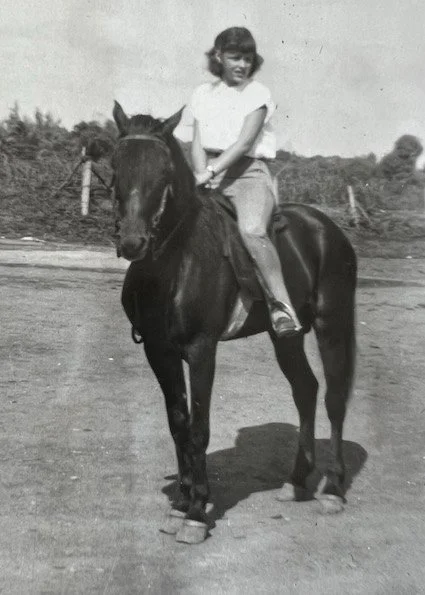

Jo DeYoung riding the Tennessee Walker colt Danny in DeRidder, La., Dec., 1953 Photo copyright Col. Guy O. DeYoung Jr.

My mother, still terrified of horses, leaves my baby sister with the neighbors, and pursues the horses on foot without success until the highway patrol intervenes. Shorty is exchanged for a young Tennessee walking horse named Dan.

Dan is two years old and so obedient he is immediately stolen. When I go out to the pasture to get him on his second day, the other horses are grazing, and he's gone. The horse pasture lies just outside a neighborhood called Redbone Alley, where the children are forbidden to go. I walk up and down the streets looking for Dan because I can't really think of anything else to do, and I’m surprised when I find him tied up in someone's back yard. A family is out in the driveway. I walk past them, untie my horse, and take him home. No one says anything, and I don’t tell my parents. Two months later, we sell Dan because our family has to move again.

My baby sister, Elizabeth Anne, who will yearn for horses but never get one, grows up on stories about Shorty and Dan. When I go away to college, she draws pictures of the horses she has never seen and sends them in the letters she writes. "You were the lucky one," she will say every so often for the next 30 years. "You had two horses."

Jo on a Paso Fino (Photo by Col. Guy O. DeYoung, Jr.)

When we move to San Juan, Puerto Rico, I discover the beautiful Paso Fino horses so prized on the island. A breeder who lives in Rio Piedras, near the University of Puerto Rico, lets people who come to see his show horse go out for trail rides on others, accompanied by a guide and paying by the hour.

The horses are gentle. They have a smooth walk and trot, easy for a beginner to ride. My favorite is a bay named Coquito. The rides are expensive and rare, but they are highlights of my life.

During this time, a cousin of mine who lives in the states sends me a subscription to the Arabian Horse magazine. It is a revelation. Right there, on the cover, are the horses I have always imagined, with large dark eyes, tiny muzzles that could fit in your hand, and long, thick manes and tails. Arabians. I look at their pictures month after month, and my dreams change a little. The dappled gray mare I want is an Arabian.

Years pass, in life as in fairy tales, and I have other obsessions. I marry. We are a family with two daughters. Without much planning, I have a 40-year career as a newspaper reporter. I move constantly, living and working in Cincinnati, Detroit, Washington, Miami, London, and New York. Then I work in places like Kansas and Idaho, Arkansas, and Oklahoma, living on airplanes while my husband and daughters stay put near the University of Illinois, where my husband is a professor.

For two years, I commute every week to the Oklahoma City bombing trials in Denver. I cover murders and school shootings, hijackers, and anthrax attacks. At the end, I find myself burned out and living in a college town where I'm still a stranger, on a small urban island in a sea of soybeans and corn. As I consider what I'll do, it occurs to me that this is a place I could own a horse.

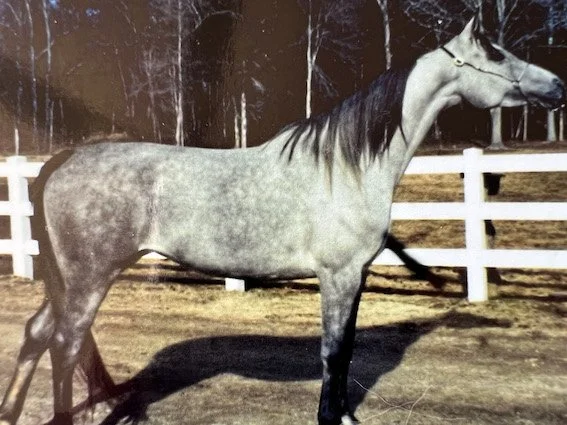

Overnight, I become reckless in the way that is possible when a dream that is lost suddenly reappears, just within reach. Without a thought, I discard the skepticism I've acquired at great cost over many years. I turn into a gambler betting on a sure thing. I know just what I want. I find my four-year-old dappled gray Arabian mare for sale on an internet website. She floats through a music video with nostrils flared, tail in the air, and I'm in love. I talk to the broker who has listed her for sale. The mare was once named grand champion mare at an Arabian horse show in Memphis. She has had 30 days under saddle and is ready to ride. She is utterly beautiful.

I ask a vet to look her over, and when he gives her a pass, I buy her without negotiating the price, without riding her, without even going to see her. I arrange with a horse transporter to bring her north from Kentucky. That girl in the brown shoes, the girl on the stick horse, the girl who could never sit in the saddle, who finally buried her love for horses so deeply that no one else knew, is going to ride at last.

There's a glitch, a small one that means nothing to me at the time. The day before the horse is scheduled to depart, the horse dealer calls to say the mare has been "naughty" that morning, has charged at the woman who is working her on a lunge line. In the scramble, the mare has tangled herself up and gotten a small rope burn—nothing serious, the dealer says. I say okay, and I wait.

Alaszka Dawn as a Dapple Gray Four-year-old

Headlights turn into the road, ruler-straight in the Illinois cornfields. I can see a long row of blue lights following behind. I am no stranger to spectacle. Up close and all around, I've witnessed riots and cities on fire. I've been caught in floods and hurricanes. I've interviewed gangsters and terrorists, and I've gone to Buckingham Palace to see the Queen. Tonight a row of blue lights is coming toward me on the road, bringing the horse I have seen in my dreams, and I can't breathe.

The driver is tired. My mare is the last one he's dropping off, and he says she's a handful. He snaps on a lead rope, and she charges out, a whirlwind of legs and shoulders, much bigger than anything I expected. Luckily, I have asked Jamie, a trainer, to be here tonight because I have read that it is important to bond with your horse from the very first, and I want Jamie to show me how.

Jamie holds the mare while I sign paperwork for the driver, who tells me my new horse kicked the hell out of the trailer on the way up. She's frightened and wild-eyed. Jamie and I pet her and try to soothe her, and I tell her that we are both home at last. Somehow, we get her into the stable.

In the light, Mary, who owns the farm, observes that the mare has a nasty cut on one of her rear legs, probably from kicking the trailer. The wound will have to be soaked, she says, and wrapped. At least three times a day.

In the warm yellow light of the barn, Mary shows me how to soak and rinse the leg as the mare dances nervously. She puts gauze on the cut and covers it with a wrap that must be tight enough not to slip, but not tight enough to cut off the circulation. The wrap comes in a fat roll you unwind around the leg. Mary makes it look easy, but in my fingers it will seem impossible.

I have not expected a frightened mare. I have not expected a mare that is hurt, that is big enough to trample me when I am bending, not bonding, to soak the leg she doesn't want me to touch. Alaszka Dawn is a living horse, not a living dream, and she is all mine.

As the years pass, she will turn white, she will become a mother, she will become a show horse and a local, regional and national champion, winning classes for her conformation and responsiveness as a sport horse and her talent as a dressage horse.

She will take me trail riding and, in her old age, learn to jump and take a child of ten to championships. In the last week of her life, she will give riding lessons to a child of five.

But when she arrives I do not know she is not trained to ride. In our first week, she throws me into a wall on my head at a gallop. I am wearing a helmet that cracks but saves my life. I get up and walk away.

I have a long journey to connect with the beauty that lies in her gentle heart.

Jo and Alaszka